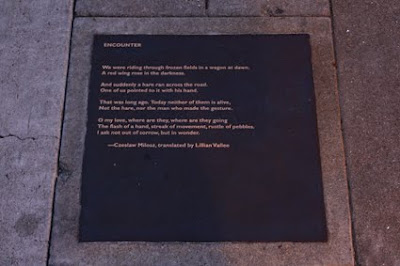

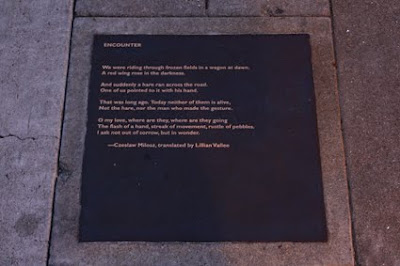

I traveled to California with Czeslaw Milosz. This Polish poet and essayist had spent over forty years in Berkeley as a professor at the California University and that’s where he wrote his best works (at least the most important for me). I have used his writings as the guide to the unknown. Or maybe in a way he was my reason for this journey and in practice whole trip was kind of a strange pilgrimage in footsteps of a dead writer. What ever it was I liked and enjoyed it.

I traveled to California with Czeslaw Milosz. This Polish poet and essayist had spent over forty years in Berkeley as a professor at the California University and that’s where he wrote his best works (at least the most important for me). I have used his writings as the guide to the unknown. Or maybe in a way he was my reason for this journey and in practice whole trip was kind of a strange pilgrimage in footsteps of a dead writer. What ever it was I liked and enjoyed it.

Milosz the most openly described his impressions from San Francisco Bay in the end of sixties. For a fresh refugee from the postwar Europe the reality of California and most of all the specificity of San Francisco Area at that time (the hippie, gay and so on movements’ center) appeared so alien that it allowed him to observe his own everyday’s live from a distance of the botanist. Today for me NYC is not so strange, probably even for Milosz it wouldn’t be - after all East Cost is much closer to Europe. However I do have some difficulties in finding the vocabulary to describe my experience of being here, in US, and Milosz’s writings became an irreplaceable dictionary and manual for my understanding of the situation. So, when we went to California I finally got a chance to compare in very detail Milosz’s and mine observations, to find and to point all the differences, to check how the landscapes described by him will resonate in my imagination.

It was an intriguing experience to go there with him. First of all a religious or better a theological poet is not the most obvious guide to the place. But his unyielding attitude toward all the authority turn out to be an efficient pass to this rebellious city. His descriptions and opinions from sixties and seventies outlined for me a sort of the place mythology, a genius loci, and gave an useful key to the place that looks at first as a reverse of the stereotype of America.

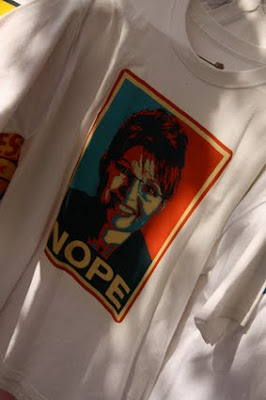

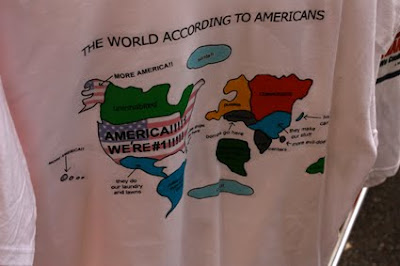

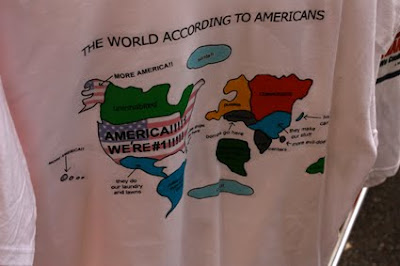

Milosz vision of America is apocalyptic and surprisingly Proustian. The immensity, potency and diversity of this country make him speechless, its beauty make him defenseless. But in Americans, also in himself there, he found the basic complex of the Marcel Proust’s heroes. They had escaped to America for sake of the freedom, prosperity and self-sufficiency. They had desired it so badly that this passion pushed them through the endless oceans, deserts, mountains, and forests. Finally the strongest ones got here and succeed to conquer the land, its inhabitants and the concurrent conquerors. Already in first, second or third generation they got what they desired at the beginning, often far more that they could ever imagine in their villages in Europe or Asia. In addition at one point, some of them sooner some later on, they got something they had abandoned when they had started to move – the sense of safeness. And then they, their children, us find themselves at the very same starting point. Fulfillment of the original desire don’t bring the satisfaction. To the contrary – it causes the inevitable disappointment and only very rarely the conscious disillusionment. So the children of the cowboys become hippies and the children of hippies become … and so on. At the end of every turn we always find this same disgust and emptiness. The apocalyptical difference is only that by reaching this place the conquerors had discovered a totally new scale. Wherever they will turn now their footsteps will left far deeper marks and their march will trample more then ever before.  Berkeley seemed a great spot for those observations – an intellectual center in the westernmost part of the country – at the place where human urge found a natural limit – the ocean shore; where the ideas and passions which pushed people until here have to be reverse. The very turning point, or at least quite often the one. Probably fifty years ago it was more evident then today, but the political, social or cultural agitation can be still felt on the Telegraph avenue.

Berkeley seemed a great spot for those observations – an intellectual center in the westernmost part of the country – at the place where human urge found a natural limit – the ocean shore; where the ideas and passions which pushed people until here have to be reverse. The very turning point, or at least quite often the one. Probably fifty years ago it was more evident then today, but the political, social or cultural agitation can be still felt on the Telegraph avenue.

We spent whole day in Berkeley. Beside visiting the University Campus and downtown (when the rest of the group went to prepare St Urho’s day) I wanted to see the house where Milosz had lived until nineties. Far more important than the building was an area, the garden and above all the famous view from his windows to the San Francisco Bay, which found its way to so many of his poems. Irresponsibly I rejected the idea of getting there by the city bus. The distance to the address given by a Milosz’s friend didn’t seem too long… His house was at the Grizzly Peak Blvd, a long scenic drive running along of the top of the hill. And I thought that it will be enough to climb the hill behind the campus. I tried and it went nicely. I passed the Greek amphitheatre, the stadium and many university buildings. The road twisted up the hill by a large park. Sometimes in place of twirl by the drive one could shorten the way by climbing up the handy stairs. When I was almost on the top, passing by some anonymous laboratories, I was stopped by the university guard. Apparently to get where I was one needed to have a special pass: the area was supposed to be strictly guarded and the laboratories were top secret. When they were carrying me downtown to the guards station they couldn’t understand how it had happened that I hadn’t seen/pass any of the numerous gates and that no one had notice me before them. At the station they checked my passport and visa, were almost about to contact Polish Consulate. I can’t clearly recall how I managed to convince them that whole affair wasn’t so serious and that it will be enough if they remove from my camera the photos of the protected areas. Finally they let me go. I was once more down the hill. They showed me which way I can take if I want to go to the Grizzly Peak – of course few times longer than my first one. After all there was nothing else to do than climb once more. At the beginning of the sunset, after few kilometers of hiking I reach the Peak at last. The weather was wonderful: worm, even hot day was going to end. The golden rose air was moving in the heat. Since few hours I had anything to drink, I started to be hungry and tired of walking. And there it was: the splendid view to the Bay immersed in the folly of the gold, violets and grey, full of the scent of the blossoming trees.

Apparently to get where I was one needed to have a special pass: the area was supposed to be strictly guarded and the laboratories were top secret. When they were carrying me downtown to the guards station they couldn’t understand how it had happened that I hadn’t seen/pass any of the numerous gates and that no one had notice me before them. At the station they checked my passport and visa, were almost about to contact Polish Consulate. I can’t clearly recall how I managed to convince them that whole affair wasn’t so serious and that it will be enough if they remove from my camera the photos of the protected areas. Finally they let me go. I was once more down the hill. They showed me which way I can take if I want to go to the Grizzly Peak – of course few times longer than my first one. After all there was nothing else to do than climb once more. At the beginning of the sunset, after few kilometers of hiking I reach the Peak at last. The weather was wonderful: worm, even hot day was going to end. The golden rose air was moving in the heat. Since few hours I had anything to drink, I started to be hungry and tired of walking. And there it was: the splendid view to the Bay immersed in the folly of the gold, violets and grey, full of the scent of the blossoming trees. The number of the first house on the way was 1679, I needed to get to the one on 978… Well, it took a while, but the way was just beautiful. On both sides more or less fancy houses hidden in the blooming gardens, and the never-ending view to the bay, to the skyline of San Francisco, to the Golden Gate bridge, to the green and red hills, above all to the gray gloomy ocean.

The number of the first house on the way was 1679, I needed to get to the one on 978… Well, it took a while, but the way was just beautiful. On both sides more or less fancy houses hidden in the blooming gardens, and the never-ending view to the bay, to the skyline of San Francisco, to the Golden Gate bridge, to the green and red hills, above all to the gray gloomy ocean.

When I stood in front of the gate numbe r 978 there was the last moment of the spectacular sunset – as if everything was just as it should be. There was no one inside. The house was one of the older, modest and smaller then all the others. It was also probably the most neglected in the whole area. From the drive there is first the house and then to the west descend the garden opening the view to the bay. Longing for the Lithuanian forest Milosz had planted many trees there. In unkept garden they grew really tall, and today are a hallmark of the place. Apparently neighbors didn’t follow Milosz example and simply didn’t interrupt their views. On the sunny and chic Californian hill the house of Polish poet looks like a common forester‘s lodge.

r 978 there was the last moment of the spectacular sunset – as if everything was just as it should be. There was no one inside. The house was one of the older, modest and smaller then all the others. It was also probably the most neglected in the whole area. From the drive there is first the house and then to the west descend the garden opening the view to the bay. Longing for the Lithuanian forest Milosz had planted many trees there. In unkept garden they grew really tall, and today are a hallmark of the place. Apparently neighbors didn’t follow Milosz example and simply didn’t interrupt their views. On the sunny and chic Californian hill the house of Polish poet looks like a common forester‘s lodge.

When I turned there was a bus stop on the other side of the drive. After few minutes in the darkening twilight I rode the bus downtown to get some freshly made munkki.

L.

It seems much more urgent to drive a car when you are in San Francisco than in New York City. Nonetheless the good public transportation system in the city, when you talk with locals about a trip outside the city they can’t imagine it without a car. At least the most of them. Yet it was indeed possible, and despite that several times we considered to rent the car we managed without it. Probably that way was even more adventure. So we get to know the bunch of Californian buses and ferries. Sure, we were also walking a lot. And it was because of this walking that we discovered an impressive popularity of the old and bizarre cars keeping among the habitants of San Francisco…

It seems much more urgent to drive a car when you are in San Francisco than in New York City. Nonetheless the good public transportation system in the city, when you talk with locals about a trip outside the city they can’t imagine it without a car. At least the most of them. Yet it was indeed possible, and despite that several times we considered to rent the car we managed without it. Probably that way was even more adventure. So we get to know the bunch of Californian buses and ferries. Sure, we were also walking a lot. And it was because of this walking that we discovered an impressive popularity of the old and bizarre cars keeping among the habitants of San Francisco…

In the deserts of southern California and Arizona, the very thought of stopping for anything but gas or food seems absurd - why bother when you can see everything you need to out the window? There is nothing out there beside stunted, prickly vegeration. Though the coniferous forests in the Sierras is attractive, with its greenery and shade, it too, after a few steps, kills any desire for a walk amid its scree-covered tracts, rocks, inaccessible thickets. But our active passivity is also felt in relation to people. We pass them, busy with their daily work, immersed in their houses and little towns. We converse with them when we stop - in stores, restaurants, motels - but differently from the way people did when they traveled by camel, horse, or stagecoach.

In the deserts of southern California and Arizona, the very thought of stopping for anything but gas or food seems absurd - why bother when you can see everything you need to out the window? There is nothing out there beside stunted, prickly vegeration. Though the coniferous forests in the Sierras is attractive, with its greenery and shade, it too, after a few steps, kills any desire for a walk amid its scree-covered tracts, rocks, inaccessible thickets. But our active passivity is also felt in relation to people. We pass them, busy with their daily work, immersed in their houses and little towns. We converse with them when we stop - in stores, restaurants, motels - but differently from the way people did when they traveled by camel, horse, or stagecoach. They do not bring us into their tents, they don't set out feasts in honor of their guests, who are precious because they are rare. The banal ritual of greetings and goodbyes, so smooth that we pass each other like pebbles roundes by a stream, puts a distance between us and them, and so their eyes, mouths, movements are all the more disturbing to us. They are enigmatically self-enclosed, and haunt our minds as if we were from another planet, staring at humans" - C. Milosz Visions from San Francisco Bay 1969

They do not bring us into their tents, they don't set out feasts in honor of their guests, who are precious because they are rare. The banal ritual of greetings and goodbyes, so smooth that we pass each other like pebbles roundes by a stream, puts a distance between us and them, and so their eyes, mouths, movements are all the more disturbing to us. They are enigmatically self-enclosed, and haunt our minds as if we were from another planet, staring at humans" - C. Milosz Visions from San Francisco Bay 1969